Exploring Jenkins Pipelines: a simple delivery flow

In the previous post, we have created a job that triggers Selenium tests using Jenkins and its Pipeline plugin.

As it covers an important element of a CI/CD flow, it is only a small part of the whole delivery process.

In the Techniques section of the ThoughtWorks’ Tech Radar we can read that pipeline-as-code is a concept worth adopting in the industry.

That is why I would like to play a bit more with Jenkins Pipelines, to present some challenges and proposed solutions on how to apply our build scripts using this particular tool.

Key takeaways:

- You will create a complete simple delivery pipeline for an example application using Jenkins Pipelines

- You will play a bit with Docker: create, run and kill few containers

- In the end, you will have a full ecosystem, ready to be tinkered and experimented with

- You will hear some of my rants about designing delivery flow and using few terms related to CD ;)

A few words about designing pipelines

Before diving into our script directly, just like with a regular application code, first, it is always worth to think about the whole thing we are about to implement ;).

What is great about delivery pipelines is that it is a concept that is easily visualized and working top-down during the design helps a lot. That is why whenever you are working with defining such flow, remember to make use of those whiteboards hanging around your office, flipcharts or even a regular piece of paper.

Think about each stage and step within it, analyze all the elements, try to predict possible problems and most importantly - do it with your team.

In case you happen to be the one responsible for the definition, keeping it only to yourself or merely discussing specific parts with people most experienced in that area will lead to a total lack of awareness of what and when is happening in your pipeline.

It is a lesson learned the hard way in my case - do not assume people will jump to fix a failed build when the only thing they know is that… it failed: there are some stages, weird tasks executed inside them, there may even be a stacktrace or a nice error message. Without important background knowledge though, they will not feel comfortable enough to spend their time to pursue the investigation further and assume you will take care of it - you are the one that created it in the first place, you know what’s going on, right?

Treat your pipelines as a regular item in your development process, it is yet another piece of code your team is delivering. Sure, it does not end up as a nice web application that client requested but this script makes building, testing and delivering this app possible.

Set up design sessions, create the necessary tickets in your backlog, put the scripts through code review process - spread the knowledge. Every single member of your team needs to know how you guys are building it, what tests are run, how the app is released and how is the deployment made.

This way a failing build is ought to receive attention from the team - everyone will know what the cause was or at least where to look further.

The actual design

Having said that, let’s start designing our pipeline.

In the most general way, a delivery flow is usually defined as:

- Build the application

- Test it

- Deploy the application to the target server

Naturally, this gets a lot complex, since we have multiple development environments for different purposes, we want to release and tag the codebase in the process to have a straightforward way of pointing to a specific version etc. The general idea stays the same though.

Assumptions

Now, let’s provide some context for our little playground. We need to decide on few things:

- The application itself! What will serve as our test subject?

- The development process - this is one the biggest factors when devising a delivery pipeline. It includes:

- our development environments - where the application needs to be deployed;

- types of tests we will run automatically during the pipeline.

The application

For the purpose of this post (and few next :)), we will be using a simple Java application based on Spark Framework (not Apache Spark - the naming is quite unfortunate in this case): sparkjava.com. As authors say, it is a Sinatra-inspired web framework for rapid development.

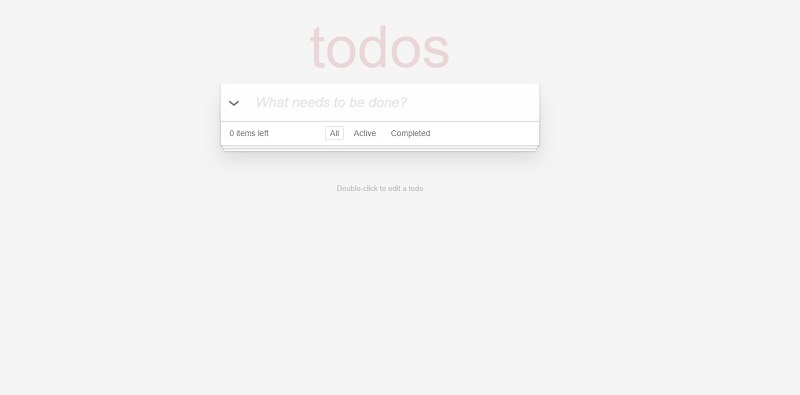

I have decided to use an existing example: a ToDo application that uses Intercooler.js, available at https://github.com/tipsy/spark-intercooler (check out the original article here). For the purposes of the post, I have forked and modified the original pom.xml to produce a ‘fat’ .jar so it can be used in the Docker context.

This sample app will expose several API endpoints and a UI so we can address testing different layers.

The development process

Since there is no development team, the whole process is going to be A LOT easier. For sake of simplicity, let’s assume that we do not want to work on branches for now - we will focus on the main branch of our repository. After building an application and deploying it, we will run automated tests and release the codebase upon a successful execution. We are keeping it simple and leave out of the equation aspects like static code analysis, additional elements of the infrastructure or more fancier aspects of development and QA :).

Environments

Wait… but where are we going to deploy the application?

That’s right: we do not have a server where we could put it. On the other hand, since we consider a lone-wolf scenario here, we do not need a shared machine available to wider audience. We will utilize Docker to spin up a container with the built application inside so there is a target for our tests to hit.

Usually, for our applications we have some sorts of ‘production’ environment - again, to not overcomplicate things, in our case, this is going to be an additional Docker container, named majestically production :).

Types of tests

The last part - types of tests we want to run in the pipeline. In this example, since we have both UI and API available for testing, for each build we will run Selenium tests (utilizing the knowledge from the previous post, using Bobcat framework) and RestAssured tests. For a few tutorials on the latter, check out related posts on TestDetective’s blog. Once again, keeping things simple, I’m not going to create different suites dedicated to verifying the deployment of ‘production’ - testing here a stateful application is a topic for a separate post.

Repository: structure and contents

An important part of designing a pipeline is to know all the resources that we need to handle - the solution used in a script may need a total refactor when you find out that e.g. the repository you just cloned has a totally non-standard structure in comparison to what your team/organization is used to have.

Let’s avoid that by planning how our repository is going to be structured from the very beginning.

And of course, we need to provide the actual contents afterward.

We will use the following structure:

.

├── app

│ ├── pom.xml

│ ├── README.md

│ ├── src

│ └── target

├── Jenkinsfile

└── tests

├── bobcat

│ ├── pom.xml

│ ├── src

│ └── target

└── rest-assured

├── build

├── build.gradle

├── gradle

├── gradlew

├── gradlew.bat

├── settings.gradle

└── src

A bunch of comments:

- the application is the aforementioned ToDo list, you can grab it from this fork

- for Selenium tests, we will be using Bobcat framework again; it can be set up the same way as we did in the previous post

- REST Assured framework, for its basic setup, please refer to its documentation or this post

- as you can see above, these three parts are separate projects, built with different tools: Maven and Gradle

Drafting the pipeline

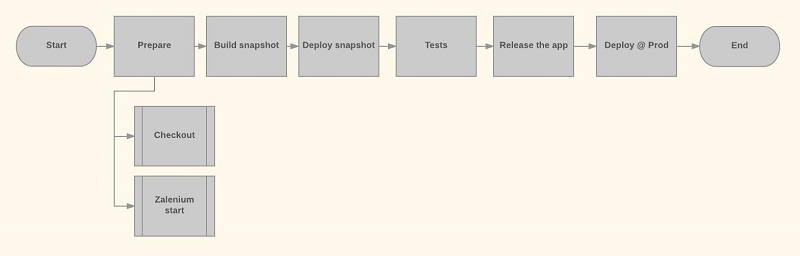

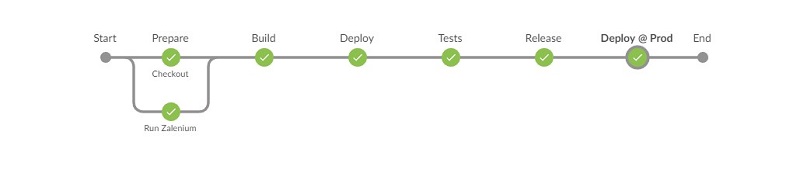

As mentioned at the beginning, let’s visualize what we are trying to achieve. Our pipeline will look as follows:

Let’s map this to Jenkins Pipelines stages (if you’re unfamiliar with vocabulary related to Pipelines, do check their docs):

node('master') {

stage('Prepare') {

parallel Checkout: {

}, 'Run Zalenium': {

}

}

stage('Build') {

}

stage('Deploy') {

}

stage('Test') {

}

stage('Release') {

}

stage('Deploy @ Prod') {

}

}

Ok, we have the basics covered, now it is time to finally move to…

Implementation!

Keeping the pipeline design in mind, let’s fill in the gaps in our Jenkinsfile.

Prerequisites

I assume you have:

- Docker installed, with Selenium Grid and Zalenium images pulled already (important! make sure you have following versions pulled:

dosel/zalenium:3.4.0a&elgalu/selenium:3.4.0, latest ones may not be compatible with Bobcat yet) - Jenkins running

- a hosted Git repository set up

The previous post contains information about setting up the above - check it out in case you miss something.

In general, it might be worth checking out the official docs if you are not familiar with Docker.

Since we will be connecting containers with each other, all containers will be launched in the host network by adding --network="host" as one of the parameters in run commands. An alternative would be to create a custom Docker network and provide addresses to specific containers manually.

In case of Docker for Windows (and Mac, based on the comments I have read) things are a bit tricky - when using the host network you will not be able to reach out the container via localhost but the host VM IP (for Windows it’s usually 10.0.75.2).

Running Docker from Jenkins container

We need a bit of tweaking in Jenkins container.

Since we will be spinning up Docker containers from Jenkins directly and due to the fact that Jenkins itself is in a container (at least this is what I’m assuming in the post :)), we need to make sure Jenkins can spawn sibling containers on the same Docker host. Since pipelines are executed as jenkins user, mounting the socket is not enough, we need to run commands as root user.

We are going to apply the method presented in this post but without writing a Dockerfile. There are other options, like running Docker-in-Docker or adding jenkins user to the docker group but after reading a bunch of comments and posts about this setup failing, I have decided on this method. Additionally, I am working on a Windows machine with Docker for Windows and possibilities here are a bit different than in a genuine Linux setup (or at least I haven’t found anything helpful - love to hear about an alternative).

Long story short, one of the easiest ways to work around the above problem is to simply add a possibility for jenkins user to execute Docker in sh steps by adding sudo. The only problem is that it is not available in the OOTB Jenkins container.

First, we need to run our Jenkins instance with additional volume that binds the socket (oh, and I recommend mounting the /var/jenkins_home volume too, to have a backup of your Jenkins configuration ;)):

docker run -d -p 8080:8080 -v /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock -v <your-dir>:/var/jenkins_home --name jenkins --network="host" jenkins/jenkins:lts

Now, re-configure Jenkins if needed and when it is up and running it’s time to hack it a bit.

Execute the following commands:

docker exec -it -u root jenkins bash- it will attach your console to bash on your Jenkins container, as a root userapt-get update && apt-get install -y sudo && rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/*- we installsudoecho "jenkins ALL=NOPASSWD: ALL" >> /etc/sudoers- thanks to thisjenkinsuser can usesudowithout providing password

And we are all set!

Now, a must-have disclaimer: this method, in general, will not win you a reward in terms of security - from the above post:

Be aware that there is a significant security issue, in that the Jenkins user effectively has root access to the host; for example, Jenkins can create containers that mount arbitrary directories on the host. For this reason, it is worth making sure that the container is only accessible internally to trusted users and considering using a VM to isolate Jenkins from the rest of the host.

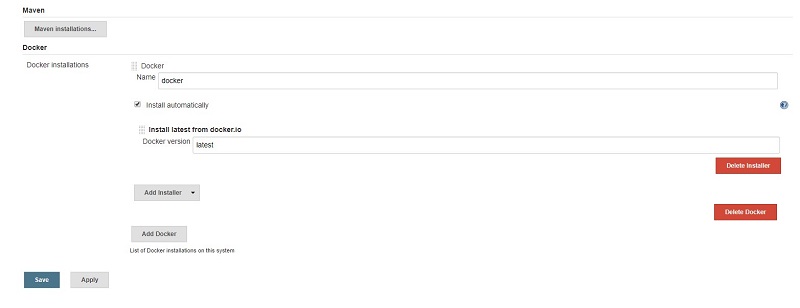

The remaining part is getting the Docker available on Jenkins itself. There are two options: use apt-get again or utilize the in-built Jenkins tool installers. Let’s try the latter.

Go to Jenkins tools configuration (

To use the installer, the easiest way will be to wrap all the stages in a withEnv block, where as an argument we will provide the path to the freshly installed Docker:

node('master') {

def dockerTool = tool name: 'docker', type: 'org.jenkinsci.plugins.docker.commons.tools.DockerTool'

withEnv(["DOCKER=${dockerTool}/bin"]) {

//stages

//here we can trigger: sh "sudo ${DOCKER}/docker ..."

}

}

Using this couple of times might get cumbersome - let’s wrap it in a method:

node('master') {

def dockerTool = tool name: 'docker', type: 'org.jenkinsci.plugins.docker.commons.tools.DockerTool'

withEnv(["DOCKER=${dockerTool}/bin"]) {

//stages

//now we can simply call: dockerCmd 'run mycontainer'

}

}

def dockerCmd(args) {

sh "sudo ${DOCKER}/docker ${args}"

}

Alright, having the prerequisites covered, we can move on to the main part of our Jenkinsfile.

Prepare

The first stage is pretty straightforward: since the pipeline itself is placed inside the same repository, we will have the necessary information stored inside the job. We can make use of the scm environment variable for the code checkout.

As for spinning up Zalenium, we just need to execute one docker run command.

stage('Prepare') {

deleteDir()

parallel Checkout: {

checkout scm

}, 'Run Zalenium': {

dockerCmd 'run --d --name zalenium -p 4444:4444

-v /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock \

--network="host" \

--privileged dosel/zalenium:3.4.0a start --videoRecordingEnabled false'

}

}

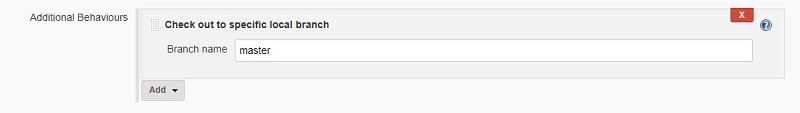

Note: when configuring the job, make sure to add ‘Check out to specific local branch’ set to ‘master’ in Additional checkout settings. Otherwise, Maven Release plugin may be less happy.

Build

The application build process is a straightforward one-liner: mvn clean package. We need to execute it in a proper directory though. It will produce a .jar file containing all necessary dependencies, together with an embedded Jetty container.

Additionally, we need to make sure our artifact will be deployable. Due to the fact that we are using Docker, we need to build a proper image, a sort of a template for containers with our application inside.

To do so, we need a Dockerfile. Create an empty one in the app folder and enter the following:

FROM java:8-jre

COPY target/sparktodo-jar-with-dependencies.jar /opt

EXPOSE 9999

CMD ["java", "-jar", "/opt/sparktodo-jar-with-dependencies.jar"]

Having the above file, we can now build an image by invoking the following: docker build --tag NAME:TAG .. The tag and version will allow us to create a container with a corresponding version of the application.

Before embedding the command into the Jenkinsfile, it is always good to verify it locally (if possible, naturally). In this case, we can easily try it out by invoking mvn clean package first, followed by the image build command. It should pass and we can confirm that our image is ready to serve as a blueprint for new containers by running docker images. The output should contain a similar entry:

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

automatingguy/sparktodo 1.0-SNAPSHOT f78abc0cdfc5 3 seconds ago 320.7 MB

Now, let’s add the above commands to the Jenkinsfile:

stage('Build') {

withMaven(maven: 'Maven 3') {

dir('app') {

sh 'mvn clean package'

dockerCmd 'build --tag automatingguy/sparktodo:SNAPSHOT .'

}

}

}

We do not care which version is being built for testing purposes, hence we went with generic ‘SNAPSHOT’ tag (in real projects, this probably will not hold true). We will override this image whenever new build has been triggered (and there were changes in the application: Docker caches the layers and reuses them whenever possible - try it out by running several subsequent Docker build commands without changing the app package).

Deploy

When it comes to the deployment, we simply need to spin up a Docker container built in the previous stage.

We do it by executing: docker run -d -p 9999:9999 --name 'spark' automatingguy/sparktodo:SNAPSHOT.

A quick explanation of used parameters:

-d- runs the container in ‘detached’ mode, meaning the current console window will not be connected to it and the container will run in the background-p 9999:9999- this binds the 9999 port on the host machine to the exposed 9999 port from the container--name 'snapshot'- thanks to this we have a handy name to use to kill the container later :)

For more information, please check out the official Docker docs.

Oh, and after going to http://localhost:9999 in your browser, you should see the landing page of our application:

The next stage in our pipeline script looks following:

stage('Deploy') {

dir('app') {

dockerCmd 'run -d -p 9999:9999 --name "snapshot" --network="host" automatingguy/sparktodo:SNAPSHOT .'

}

}

Tests

Now, having the container up and running with a snapshot version of the application, we can test if the application itself works correctly. If they pass, it means the codebase is stable and it can be released. We will reuse part of the code from the previous post:

stage('Tests') {

try {

dir('tests/rest-assured') {

sh './gradlew clean test'

}

} finally {

junit testResults: 'tests/rest-assured/build/*.xml', allowEmptyResults: true

archiveArtifacts 'tests/rest-assured/build/**'

}

dockerCmd 'rm -f snapshot'

dockerCmd 'run -d -p 9999:9999 --name "snapshoui" --network="host" automatingguy/sparktodo:SNAPSHOT'

try {

withMaven(maven: 'Maven 3') {

dir('tests/bobcat') {

sh 'mvn clean test -Dmaven.test.failure.ignore=true'

}

}

} finally {

junit testResults: 'tests/bobcat/target/*.xml', allowEmptyResults: true

archiveArtifacts 'tests/bobcat/target/**'

}

dockerCmd 'rm -f snapshot'

dockerCmd 'stop zalenium'

dockerCmd 'rm zalenium'

}

Since our tests modify the state of the application, the easiest approach is to execute them against a freshly started app. That is why we are killing and spinning up the snapshot container in the middle of the stage. We stop and remove the containers at the end since we do not need them further in the pipeline.

Important: in case of a test failure, the containers will be left alive to enable debugging what has actually happened. Afterwards, a manual cleanup will be required (or we could check for alive containers and kill them in the previous step, or append a build name/version number to them, or… there are couple alternatives :)).

Release

Ok, we know that our application works perfectly fine and there is no point in keeping it to ourselves - it’s time for a release.

Now, a small digression here.

One of the most common mistakes I encounter around delivery pipelines is people confusing two terms: release and deploy. Anyone heard “let’s do a release to production!”? By this time, you should have already noticed, that these two do not act as synonyms but two different steps in the whole delivery process.

Release != deploy.

You release a given state of the code, you deploy artifacts built from that state. A release can be stable or not, you may always discard a release - consciously decide not to deploy it. Now, you might think that it is just a rant about naming conventions. But when people treat these totally separate actions as the same thing, they tend to get into this psychological effect where they do not want to release the code because they associate it with a deployment, something they perceive as risky and complicated. It is a thing I had to fight against and constantly remind people about.

Do not be afraid to make a release. Release. Release as often as possible.

Answering the question if a given release is worthy of anything is another problem - but at least you have a concrete item to debate on.

Having that off my chest, let’s get back to the pipeline implementation :).

We will utilize Maven Release plugin, a standard way to perform such action in Maven realm. Some of the actions it does:

- Strip the snapshot part of the version

- Build the codebase, make changes in the configured SCM (Git in our case)

- Increment the version and add append

-SNAPSHOT Deploy the artifacts to the provided server- this one we will skip, as we will handle it a bit differently in our case

To do all of it, we need to tweak the pom.xml a bit. Add the following:

...

<scm>

<developerConnection>scm:git:https://github.com/mkrzyzanowski/blog-002.git</developerConnection>

</scm>

<build>

<plugins>

...

<plugin>

<groupId>org.apache.maven.plugins</groupId>

<artifactId>maven-release-plugin</artifactId>

<version>2.5.3</version>

<configuration>

<goals>install</goals>

</configuration>

</plugin>

</plugins>

</build>

...

Everything is prepared on the application side and we can test the release by executing the following in the app directory: mvn -B release:prepare -DdryRun=true.

A bunch of additional pom.xml files will be generated where we can inspect the versions injected during the release. The -B switch will run the process in a non-interactive way. You can remove the additional files with mvn release:clean.

Normally, when having a Jenkins set up in an actual project, the thing worth doing is providing settings.xml and .gitconfig files for Jenkins to use. We will skip the ‘proper’ way of handling those and inject the necessary information directly in CLI, learning how to work securely with credentials in Pipelines at the same time.

Add new credentials to the credentials store in Jenkins (<Jenkins address>/credentials/) and put there the username and password for a user with write access to the repository. Add a meaningful ID, so it will be easier to use it in the pipeline.

Additionally, we cannot forget about building a Docker image tagged with the released version so it might get deployed to ‘Production’.

The ‘Release’ stage of our script should look like this:

stage('Release') {

withMaven(maven: 'Maven 3') {

dir('app') {

releasedVersion = getReleasedVersion()

withCredentials([usernamePassword(credentialsId: 'github', passwordVariable: 'password', usernameVariable: 'username')]) {

sh "git config user.email [email protected] && git config user.name Jenkins"

sh "mvn release:prepare release:perform -Dusername=${username} -Dpassword=${password}"

}

dockerCmd "build --tag automatingguy/sparktodo:${releasedVersion} ."

}

}

}

The withCredentials block allows to securely unwrap stored credentials in Jenkins and does not expose them in the console log (they are being masked).

We need one last element to finalize this stage - prepare a deployable artifact. As mentioned already, this is going to be a Docker image, tagged with the released version. The released JAR is produced by release:perform goal, we just need to create the image.

First, we are going to need to obtain the released version. In case of Maven projects, this usually is the current version without the -SNAPSHOT suffix. Let’s script that part in our Jenkinsfile:

def releasedVersion

// ...

stage('Release') {

withMaven(maven: 'Maven 3') {

dir('app') {

releasedVersion = getReleasedVersion()

withCredentials([usernamePassword(credentialsId: 'github', passwordVariable: 'password', usernameVariable: 'username')]) {

sh "git config user.email [email protected] && git config user.name Jenkins"

sh "mvn release:prepare release:perform -Dusername=${username} -Dpassword=${password}"

}

}

}

}

// ...

def getReleasedVersion() {

return (readFile('pom.xml') =~ '<version>(.+)-SNAPSHOT</version>')[0][1]

}

Next, let’s add the Docker command. Here’s our final script:

def releasedVersion

// ...

stage('Release') {

withMaven(maven: 'Maven 3') {

dir('app') {

releasedVersion = getReleasedVersion()

withCredentials([usernamePassword(credentialsId: 'github', passwordVariable: 'password', usernameVariable: 'username')]) {

sh "git config user.email [email protected] && git config user.name Jenkins"

sh "mvn release:prepare release:perform -Dusername=${username} -Dpassword=${password}"

}

dockerCmd "build --tag automatingguy/sparktodo:${releasedVersion} ."

}

}

}

// ...

def getReleasedVersion() {

return (readFile('pom.xml') =~ '<version>(.+)-SNAPSHOT</version>')[0][1]

}

Deploy to ‘Prod’

Time to wrap up the pipeline with the remaining stage - deploy to our ‘production’. Nothing special will be done here and we can reuse the code that we have written so far in previous stages:

stage('Deploy @ Prod') {

dockerCmd "run -d -p 9999:9999 --name 'production' automatingguy/sparktodo:${releasedVersion} ."

}

Note that we have bound the production container to 10001 to avoid conflicts with the other one, dedicated to tests.

The whole pipeline

After gluing things together we end up with our final pipeline-as-code:

After pointing your Jenkins job to it and running, you should get the following nice green picture:

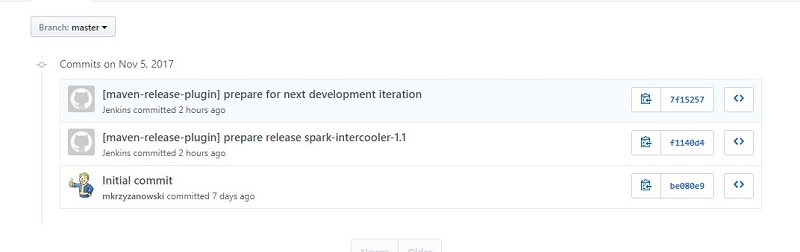

Our repository should show us the newest release, together with release-related commits:

Summary

That was a bit of a lengthy post! Let’s recap what we have done:

- we have a Jenkins in a container able to manage other sibling containers

- we know how to build a Docker image and spin up a container with sample application inside

- we have a Jenkinsfile describing a whole delivery pipeline - from code checkout, through building, testing to deploying

- we ended up with a fully functional system that can serve as a base for experiments - and for sure will serve as a base for me in the future :)

Of course, the whole codebase is available on Github.

I haven’t mentioned it in the section related to tests but the repository contains actual tests, not dummy assertions, although there aren’t that many of them. Feel free to play around and add your own checks on both UI and API level.

As you may have noticed, the code in the pipeline requires some love - there is some duplication, no proper error handling, notifications etc. Fear not - we will address these issues in the upcoming posts. Shared Libraries and configuration management are incoming!

As always, let me know in case of any comments or questions :).

Until next time!

3 Comments

Anton

awesome!

subbu

Hi,

Could you mind to tell me the source of jenkins shared libraries?

Do we get the shared libraries from cloudbees jenkins?

AutomatingGuy

They are basically an external repository with a specific structure (see: https://jenkins.io/doc/book/pipeline/shared-libraries/) and you configure them in Jenkins’ admin panel.