Exploring Jenkins Pipelines: Shared Libraries

Continuing the mini-series about Jenkins Pipelines, it is time to take a closer look at how our pipelines can follow the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle when our scripts are getting bigger and bigger, and we need to share parts of them across multiple projects. In this post, we will explore the concept of Jenkins Shared Libraries - a mechanism that allows keeping bits of our pipeline scripts within reusable units.

General information

First, let’s take a closer look at the whole idea behind Jenkins Shared Libraries. The official documentation can be found here. It thoroughly describes the general concept, but some details may not be so apparent when trying to pull pieces of your script code into a library.

Library structure and contents

Taking a look at the directory structure, it maps to the three types of elements of a library:

-

/vars- over here global variables and functions are kept - this will be your bread and butter for creating your own custom DSLs inside your scripts.After a successful run of a pipeline using a library containing such elements, they will be listed under

<jenkins-url>/pipeline-syntax/globalspage and, when a corresponding.txtfile is inside the library, present additional documentation from it - this way you can provide extra help to other team members using your API. /src- a regular Java source directory; everything kept here will be added to the classpath during script compilation; the available classes can be loaded with an import statement;/resources- additional non-Groovy/Java files that can be loaded vialibraryResourcestep

The order I’ve put the above folders is not random - I’ve based it on the frequency I have been using them when working with Pipelines. That’s me - maybe your use case will be different :). I have noticed though that in general, managing steps via global methods in vars folder is more straightforward - you can use freely other steps, while the code from src requires passing the steps object from the pipeline itself.

What’s noteworthy is that all scripts are put through CPS (continuation-passing style) transformation - the magic that enables pipelines to survive a restart and occasionally make you pull your hair off due to the related errors :).

Ways of loading libraries into your scripts

We configure the Shared Libraries on Jenkins’ main configuration page - we need to provide a name and SCM details to have a way to refer to our library from the script.

The most important part here is also mentioned in the official doc: such libraries are considered ‘trusted’. There might be a chance that if you developed pipelines you’d run into problems when calling internal Jenkins or Java/Groovy APIs, where Jenkins failed the pipeline saying something about the sandbox, rejection, lack of permissions, etc. This is because pipelines scripts kept, e.g., directly in the job (which is one of the ways to debug parts of your pipelines) are run in a Groovy sandbox that is the cause of all these ‘pleasures’. Using Global Libraries solves that problem but bear in mind (if you missed this info in the docs) people with push permissions to the repository containing the Global Library have basically unlimited access to Jenkins. You have been warned, and hopefully, this is not a reason for your InfoSec team to ban Pipelines or libraries from being used.

One additional thing when it comes to a Library configuration - you can select the checkbox which loads it implicitly, meaning you do not have to worry about remembering about loading it manually. If you have some libraries that are must-haves in your pipelines that may be an excellent improvement to your workflow.

Since libraries are yet another bunch of code, you might want to version them by tagging the repository or keeping different branches active - you can specify the default revision in the configuration (which probably is a good idea when combined with implicit loading).

If like me, you prefer to control the whole pipeline from the code, you can load the library using @Library annotation. It can be put above one of your import statements or (in case you are using only global variables/functions) with an underscore: @Library('your-lib') _.

There is an additional step that loads a library dynamically during the runtime: library 'your-lib'. Keep in mind though, that with this approach all your library classes have to be accessed via a different method: library('your-lib').com.company.SomeUtil.method(). I haven’t found a use case for such approach yet, so let me know when you needed to load a library like that!

Refactoring time!

Now that we know the basics, it is time to apply them to an actual script! Let’s analyze the pipelines that we created in previous posts - they should give us at least couple points that we could refactor. Here are the pipelines:

Creating a library

As I mentioned before, a library is merely a code repository with a specific folder structure so first let’s create a simple Git repository. Now, what shall we put inside?

Finding candidates for a library

When thinking about moving parts of your pipeline to a library, imagine creating a similar script in the next project or creating an additional pipeline that reuses bits of the one you already have. What can/should be extracted to make that possible or painless? Keep in mind that when scaling your delivery pipelines you probably want to introduce a change in a few places as possible.

Now, let’s take a look at following elements in the above scripts, our potential candidates that we can delegate:

- Methods defined inside the script:

dockerCmdandgetReleasedVersion - The way we run tests

- The release procedure

Methods defined in the script

The first on our list are the methods that we defined in our pipeline. They are usually the most obvious candidates to be moved to a library - it is a piece of logic that has been already extracted out of the main script body. Naturally, sometimes such methods will make sense only in the context of the given pipeline, where they will stay.

Let’s focus on the getReleasedVersion method, as this one will be easier to handle:

def getReleasedVersion() {

return (readFile('pom.xml') =~ '<version>(.+)-SNAPSHOT</version>')[0][1]

}

It does not depend on any additional environmental variables, it just reads and processes a POM file. Assuming we leave navigating to it to the pipeline, we can basically almost copy-paste it into the library.

To do so, we need to create a small Groovy script in our still empty repository. Since we would like to re-use the above as a regular step in the pipeline, we will put it inside vars folder and name the file just as our step will be invoked: getReleasedVersion.groovy. The contents will be a simple call function, without any parameters (for simplicity/laziness reasons :)):

def call() {

(readFile('pom.xml') =~ '<version>(.+)-SNAPSHOT</version>')[0][1]

}

And that’s it, we have the first step in our shared library! On to the next one then.

The dockerCmd is a more tricky case. The definition might not be, but let’s see how it is being invoked:

//...

def dockerTool = tool name: 'docker', type: 'org.jenkinsci.plugins.docker.commons.tools.DockerTool'

withEnv(["DOCKER=${dockerTool}/bin"]) {

//...

}

//...

def dockerCmd(args) {

sh "sudo ${DOCKER}/docker ${args}"

}

The dockerCmd depends on the environment variable DOCKER, which on the other hand requires a Jenkins tool properly configured. We could simply move the function as is, perhaps with an additional safeguard throwing an exception when such variable is missing but imagine using such step in another pipeline. You probably would copy-paste these two lines (who would remember in what package lies the type of the tool?). This is not the most user-friendly approach, right? But perhaps we could wrap them in a single handy call, like… withDocker?

Let’s create two additional global steps in our library:

-

withDocker.groovy:def call(Closure body) { def dockerTool = tool name: 'docker', type: 'org.jenkinsci.plugins.docker.commons.tools.DockerTool' withEnv(["DOCKER=${dockerTool}/bin"]) { body() } } -

dockerCmd.groovy:def call(args) { assert DOCKER != null assert args != null return sh(script: "sudo ${DOCKER}/docker ${args}", returnStdout: true) }

The additional return here might come in handy when we would like to use the returned information (e.g., container ID) somewhere further in the pipeline.

Save, commit and we’re done. Having the above, we can now directly call, e.g.:

withDocker {

//...

dockerCmd 'run -d -p 9999:9999 --name "snapshot" --network="host" automatingguy/sparktodo:SNAPSHOT'

//...

}

The way we run tests

The next element on our list is how we run specific tests in our pipelines. Usually, in your team or organization, you will have to execute the tests the same way multiple times - there are various environments, different groups reuse the same test automation frameworks, etc. Such executions are perfect bits that can end up in a library.

In our pipelines, we have executions of two frameworks, Rest Assured and Bobcat:

try {

dir('tests/rest-assured') {

sh './gradlew clean test'

}

} finally {

junit testResults: 'tests/rest-assured/build/*.xml', allowEmptyResults: true

archiveArtifacts 'tests/rest-assured/build/**'

}

try {

withMaven(maven: 'Maven 3') {

dir('tests/bobcat') {

sh 'mvn clean test -Dmaven.test.failure.ignore=true'

}

}

} finally {

junit testResults: 'tests/bobcat/target/*.xml', allowEmptyResults: true

archiveArtifacts 'tests/bobcat/target/**'

}

Let’s assume that we will execute them using Gradle and Maven respectively.

Taking a look at the above code snippets in the context of extracting them to an external function, parametrizing the paths used in them is probably a good idea. We will leave the dir steps out of the library though - in my opinion, it is the responsibility of given pipeline to know the context of a given stage and navigate correctly through its workspace.

Just like with any other library that we would implement when creating steps for Jenkins, it is always a good idea to stop for a second and think about possible and relatively cheap extension points. What could be a bit different use case of the step we are trying to introduce? What modifications our user might need in the future? How would we like to adjust triggering the above code?

In general, the most common case when it comes to executing Maven/Gradle or other build system are the parameters we provide. Let’s try to include a capability that allows that in our steps.

Keeping in mind all the above, we can create two new scripts (same as before, in vars folder):

-

restAssured.groovydef call(Map config) { try { sh "./gradlew test ${config?.params ?: ''}" } finally { def path = config?.artifactsPath?.concat('/') ?: '' junit testResults: "${path}build/*.xml", allowEmptyResults: true archiveArtifacts "${path}build/**" } }We are using here a bit different construction for passing parameters. Thanks to the above syntax, we can invoke the new step in a following, more understandable way:

restAssured params: '-Psuite=MyTests' artifactsPath: '/some/directory'.Additionally, note one more significant thing: I have removed the

cleantask. I did it so this step can be safely used inparallelblocks - otherwise, such executions would wipe results from the other runs.Oh, and remember about swapping single quotes for double ones to make string interpolation possible.

-

bobcat.groovydef call(Map config) { try { sh "mvn clean test -Dmaven.test.failure.ignore=true ${config?.params ?: ''}" } finally { def path = config?.artifactsPath?.concat('/') ?: '' junit testResults: "${path}target/*.xml", allowEmptyResults: true archiveArtifacts "${path}target/**" } }We applied the same rules here, with the exact two parameters, which adds a nice consistency in our library.

Looking at the above code snippets we can clearly see that they are very similar - the try-finally, junit and archiveArtifacts steps. We could refactor both scripts even further and extract an additional wrapping step, named, e.g. testWithJunit, to make life easier for another framework - I’ll leave that exercise to you though :).

The release procedure

Time for the last part - the release procedure. Let’s analyze it (and imagine that this is a regular way of making releases in our team/organization, so putting this in the library is justified):

withMaven(maven: 'Maven 3') {

dir('app') {

releasedVersion = getReleasedVersion()

withCredentials([usernamePassword(credentialsId: 'github', passwordVariable: 'password', usernameVariable: 'username')]) {

sh "git config user.email [email protected] && git config user.name Jenkins"

sh "mvn release:prepare release:perform -Dusername=${username} -Dpassword=${password}"

}

dockerCmd "build --tag automatingguy/sparktodo:${releasedVersion} ."

}

}

At this point, you probably already noticed what and how we are going to extract :). Time to create release.groovy in vars folder!

def call(Map config) {

withCredentials([usernamePassword(credentialsId: config.credentials, passwordVariable: 'password', usernameVariable: 'username')]) {

sh "git config user.email ${config?.email ?: '[email protected]'} && git config user.name ${config?.username ?: 'Jenkins'}"

sh "mvn release:prepare release:perform -Dusername=${username} -Dpassword=${password}"

}

}

Setting up the library in Jenkins

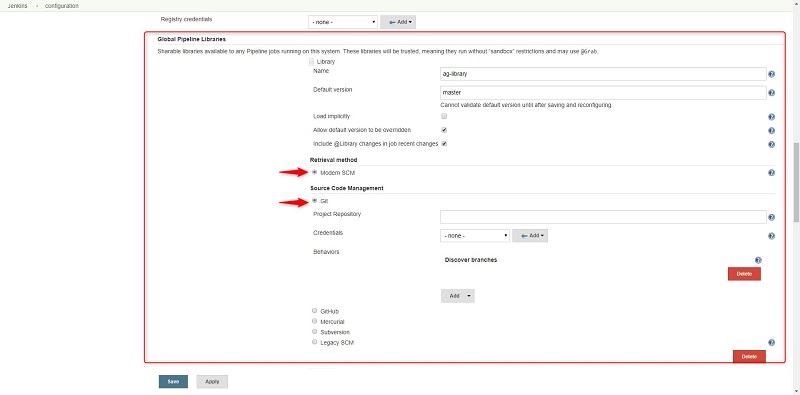

To actually use the library, we need to configure it first. Navigate to the Jenkins configuration page (/configure) and in the ‘Global Pipeline Libraries’ hit the ‘Add’ button. Now, provide a name that can be used to import it later on and, after selecting the ‘Modern SCM’ option, information about your library repository:

After this, we are all set!

Using a library in your script

Now that the hard part is finished, it is time to clean up our pipelines. We are going to replace parts of the script with corresponding library methods and add the necessary imports.

After the refactoring our pipelines look as follows:

Looking at the code above, we made it a bit more concise and easier to read. We could probably refactor it further and, e.g., name specific Docker commands. Always stop for a second and think though - is it really worth moving everything to a library?

Summary

I hope that I showed you that extracting the most common tasks and sub-processes from your Jenkinsfiles into a library is straightforward and will speed up the development of your next pipelines, at the same time giving only a single point of modification (not of failure, hopefully :)). Creating your own DSL will bring consistency and allow you to avoid reinventing the wheel each time a team starts their journey with pipelines.

Give it a try, play around with the library and do not get discouraged if you see stacktraces all over the place. Jenkins is not really verbose when it comes to errors (I encountered this beauty when working on the script here - the reason? a small typo, of course).

As usual, all the code is available at GitHub:

- the library itself: link

- repository from previous post in the series with an updated

Jenkinsfile: link

Until the next time - feel free to contact me in case of any questions/comments!

8 Comments

Ahmed

Man, thanks a lot for this guide. Yesterday I’ve discovered Multibranch pipelines and shared libraries but the most part of guides are complex and wrote in a non-human language. Your’s is the coolest of them. THANKS!

AutomatingGuy

I’m happy to hear that and glad it was helpful :)!

Meeech

Hi Michal,

One use case for using dynamic library is if you want to use another custom lib in your lib. Using the @LIbrary annotation doesn’t seem to work for that use case. (Jenkins tells me the lib isn’t found) when it clearly is there at runtime.

AutomatingGuy

Thanks for the info, I haven’t encountered such use case yet :)!

Alexa

Have you found a good way to dynamically load a branch of said global libraries without having to use ‘@branch-name’ at the end? I have multiple people who might fork/branch the global libs and it sort of seems like a pain… short of everyone adding their own global lib configuration or constantly updating their @Library calls (… and then remembering to put it back before submitting their PR’s…) I’m not really sure how you handle this gracefully. Loading libs at runtime is a non-starter, need the classpath and everything in src/.

AutomatingGuy

So far I’ve been living with the same pain :/. It’s a hidden advertisement of trunk-based development :D.

But right now with JCasC here, it might be worth to keep the branch info in the library configuration, swap it in the config file (see my post about JCasC: https://automatingguy.com/2018/09/25/jenkins-configuration-as-code/), test it locally on a Jenkins instance configured in a universal way, then merge the working stuff to master! This way, you can simply reference the library with

@Library('your-lib'):).Jean-Luc

Hi,

Thanks a lot for this clear and didactic post. Nevertheless I have a question about libraries. If I correctly understand, it seems that the library must be at the root of a git repo. Working in a complex / constrained environment, I need to store my library in a (les’s say)

continuousIntegrationdirectory which is not at the root level. I don’t understand in the configuration page how I can achieve that, as far as it seems that it does not offer the possibility to enter a directory path.If I am wrong, any explanation would be appreciated. If I am right any suggestion would be welcomed.

Thanks for your help Best Regards J-L

AutomatingGuy

Yeah, unfortunately the Shared Libraries and their structure is a bit strict :(. I guess this hack might help in your situation: link. Otherwise, you could try to forfeit the Shared Library concept and load Groovy files in your Jenkinsfiles from a folder, as shown here: link.